Here are 10 questions to ask yourself when giving a gift:

1. Why am I giving it?

2. Is it sincere?

3. Am I giving it without strings attached?

4. Does it reflect the receiver’s taste—not mine?

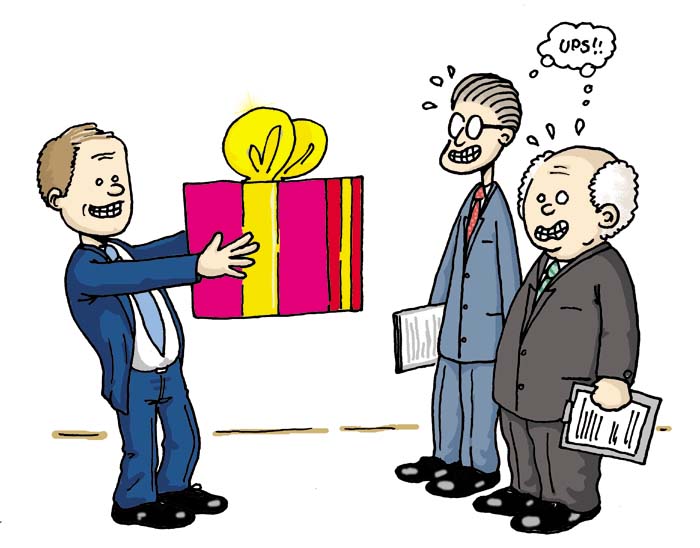

5. Is it too extravagant?

6. Is it kind? (Beware of gag gifts.)

7. Is it appropriate? (No candy for a dieter.)

8. Can I present it in person?

9. Is it presented beautifully?

10. Do I feel good about giving it?

Let’s expand a bit on the first point, which is really the most important consideration. The first question you should ask yourself is why you’re giving the gift. We give gifts to say thanks to a business associate for an introduction, to someone who gave a lunch or dinner in our honor, to a couple for dinner at their home, to a person who gave us information that helped land business, or to someone who treated us to dinner.

You might also give a gift to congratulate someone on a promotion, an award, a marriage, a birth, an anniversary, or a birthday. And when choosing a gift, don’t forget the reason you are giving it. Fortunately, there are lots of ways to find, choose, and send gifts for every occasion.

- If you’re tempted to buy a youngster war toys, check first with the parents. Some people have very strong feelings on the subject.

- Never give children pets unless you have cleared it with the parents beforehand.

- Joke gifts may get a laugh at the moment of giving, but can leave a sour aftertaste.

- The value of a gift is enhanced by the fact that it arrives on time and is nicely wrapped.

- Handwritten notes should accompany gifts. If you must include a greeting card, add a written note to whatever printed sentiment the card contains.

- A gift of money can be most conveniently given in the form of a check or cashier’s check. Cash is more appropriate for a child. When giving cash, include a note mentioning the amount in case some is lost or mislaid and to help the recipient when it comes time to send a thank-you letter. Your note can say something like “I hope these ten dollars will fund your victory pizza after the game.”

- Generally, money is a gift given by older people to younger people. It’s a good idea to try to learn if the recipient is saving for something special and to include a note saying the gift is to bring the person closer to that goal.